The reputation of John Cage rests primarily on his work as a composer. Am I wrong? Could be. For some he is a speaker, performer, and theorist whose collections of lectures and anti-lectures such as A Year from Monday and Silence have been life altering. His work in poems and anti-poems constitute another area of influence. (That “anti” stuff is clunky, I know, but his work floats on such peripheries as to make usual generic discussion impossible; see the transcription of Empty Words below). What they have in common is improvisation.

Maybe. I have been told by jazz musicians that improv in jazz is never spontaneous, is instead a very intentional process of disassembly and reassembly. Fine, then Cage’s improv goes much farther. It is based on chance. Here’s an excerpt from Marjorie Perloff’s “poetry on the Brink” about Cage:

The main charge against Conceptual writing is that the reliance on other people’s words negates the essence of lyric poetry. Appropriation, its detractors insist, produces at best a bloodless poetry that, however interesting at the intellectual level, allows for no unique emotional input. If the words used are not my own, how can I convey the true voice of feeling unique to lyric?

With thousands of poets jostling for their place in the sun, a tepid tolerance rules.

This is hardly a new complaint: it was lodged as early as the 1970s against John Cage’s writings-through—texts, usually lineated, composed entirely of citations, with source texts ranging from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake to the notebooks of Jasper Johns. Here, for example, is a passage from “Writing for the first time through Howl” (1986):

Blind

in thE mind

towaRd

illuminatinG

dAwns

bLinking

Light

thE

wiNter

liGht

endless rIde

BroNx

wheelS

Brought

thEm

wRacked

liGht of zoo

The source of these minimalist stanzas is the following set of strophes, whose erasure, based on what Cage has called the “50% mesostic” rule, uncovers the thirteen letters ALLENGINSBERG required for the vertical mesostic string. I have highlighted Cage’s chosen words, here beginning with the “B” for “–BERG.”

incomparable blind streets of shuddering cloud and lightning in the mind leaping toward poles of Canada & Paterson, illuminating all the motionless world of Time between,

Peyote solidities of halls, backyard green tree cemetery dawns, wine drunkenness over the rooftops, storefront boroughs of teahead joyride neon blinking traffic light, sun and moon and tree vibrations in the roaring winter dusks of Brooklyn, ashcan rantings and kind king light of mind,

who chained themselves to subways for the endless ride from Battery to holy Bronx on benzedrine until the noise of wheels and children brought them down shuddering mouth-wracked and battered bleak of brain all drained of brilliance in the drear light of Zoo

Cage’s elliptical lyric functions as both homage and critique, subtly interjecting his own values into the exuberant, hyperbolic Howl. As hushed and muted as Ginsberg’s baroque “ashcan rantings” are wild and expansive, Cage’s poem is a rhyming nightsong, whose referents are elusive, with only the movement toward the “BroNx” transforming the “linking” of the “blinking / light” to one that is “wRacked” with “light of Zoo.” Without deploying a single word of his own, Cage subtly turns the language of Howl against itself so as to make a plea for restraint and quietude as alternatives to the violence at the heart of Ginsberg’s poem.

There is further dialogue between the two poems. For Ginsberg, sound and visual configuration support the poet’s exclamatory particulars, the urgent things he wishes to say, whereas for Cage poetry is, by definition, first and foremost a visual and sound structure. Poetry is not poetry, as he put it, “by reason of its content or ambiguity but by reason of its allowing musical elements (time, sound) to be introduced into the world of words.”

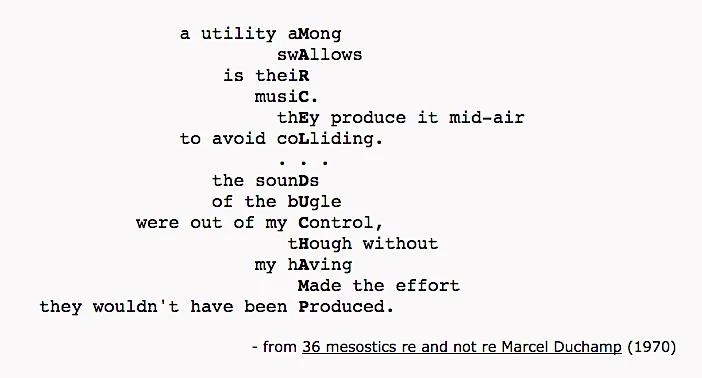

Cage’s mesostic may be difficult to make out there, so a graphic might work better:

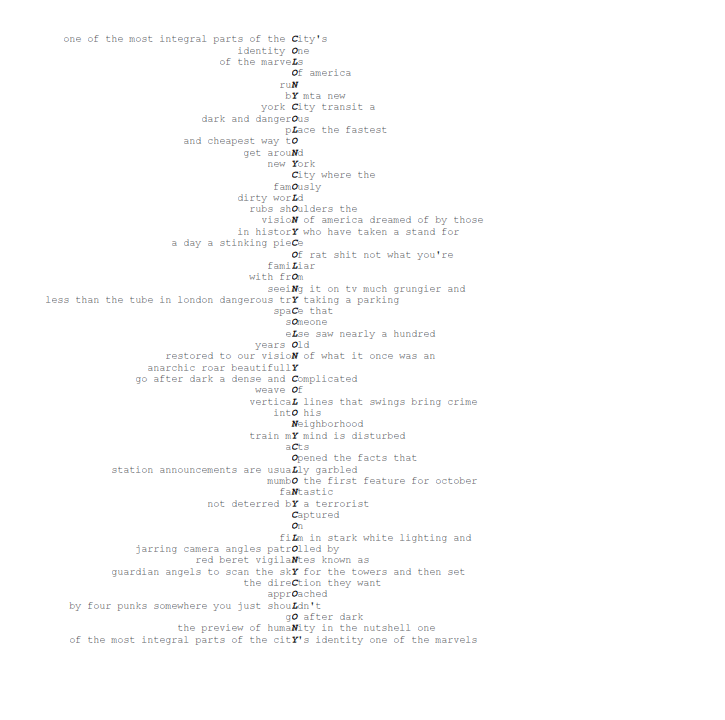

Then again, the best way to understand it might be to try to write one yourself (dare I say “anti-write” since once again, the process violates all those tropes about originality that have been drummed into us) at this site where a software program has automated the process. I’ve used it myself, enjoying the concrete nature of the form:

Just to show how far chance can go with Cage, here is an attempt to transcribe a little of his Lecture IV the fourth part of Empty Words, which, as described on his webpage: “a marathon text drawn from the Journals of Henry David Thoreau. This is one of Cage’s most sustained and elaborate moves toward the “demilitarization” of language, in four parts: Part I omits sentences, Part II omits phrases, and Part III omits words. Part IV, which omits syllables, leaves us nothing but a virtual lullaby of letters and sounds.”

3 XI 325-7 ry

4 II 430-2t um

5 I 174-6 me

6 XIV 332-4 for

7 XIII 24-6 be

and so on.

It’s not “I wandered lonely as a cloud…” But then we already have that, so why not keep moving into new territory?