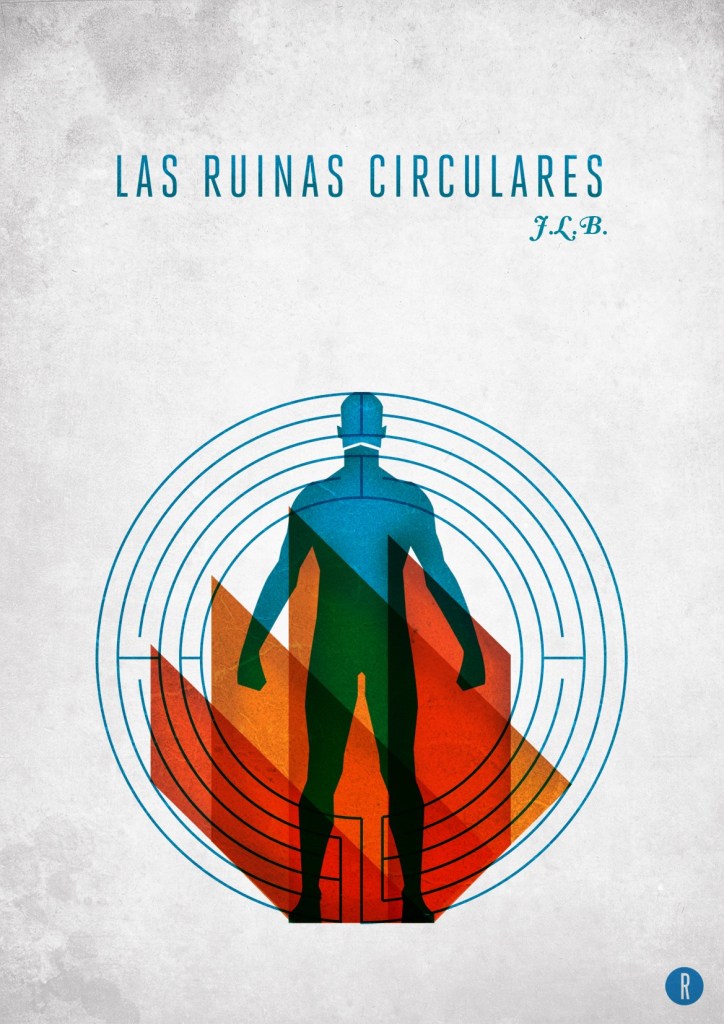

Like Frankenstein, Borges’ story “The Circular Ruins” explores the disturbing consequences of creating life, though here it is through dreaming rather than science. The narrator’s goal is to dream a man with minute integrity and insert him into reality, effectively creating a person out of dreams. Starting his task with perfect integrity, the narrator spends what feels like an infinite amount of time perfecting minute details, such as the hairs on the dream-man’s arm until the task comes to seem Sisyphean. Though the story follows a seemingly simple plot, it leads the reader in circles, reflecting the circularity of the text itself. Borges draws on a Joseph Campbell-like structure, weaving mythological elements and archetypes into the narrative. where reality and illusion blur.

The father-and-son angle serves as a meditation on parenthood, creation, and the responsibilities tied to bringing another into existence. A god of fire, reminiscent of Prometheus, grants the narrator the power to fulfill his purpose of creation but twists the myth into a realization that the creator himself is also a dream. Realizing you’re a dream is one of the story’s most profound moments, leaving the narrator as a trapped figure in endless circularity. As the narrator views his dream-man with both love and detachment, much like a parent might, the narrator reflects on his own decay and the fleeting nature of existence, transforming from the color of fire to that of ashes. Further, Borges’ description of the narrator as a grey man emphasizes his ethereal and enigmatic nature.

Borges integrates folkloric references, such as a Cornish legend, to tie his narrative to timeless myths and universal themes. The phrase “tributaries of sleep” poetically conveys the flow of dreams that feed into the narrator’s creative process. Weaving a rope of sand illustrates the futility and fragility of his task, highlighting the ephemeral nature of dreams. Coining the faceless wind suggests an attempt to shape something intangible and formless, like identity or reality.

As with The Company in “The Lottery of Babylon”, the creator in “The Circular Ruins” seems to possess all-encompassing knowledge, operating with a mysterious, almost divine authority. The ruins in the story evoke a sense of a lost religion that, paradoxically, somehow comes true through the narrator’s act of creation. The narrator’s god is not the God of the Bible but a dream god, aligning with the story’s metaphysical and mythological focus. The dream god reflects the narrator’s belief in a divinity that exists within the realm of imagination and dreams.

The story embodies metafictional and intertextual elements common in the postmodern school, blurring the boundaries between reality, fiction, and self-awareness. Borges’ use of language captures the surreal beauty of a dream, elevating the story’s poetic and philosophical tone. Like Voltaire’s Zadig, the story explores themes of destiny, creation, and the search for meaning within a larger cosmic structure. The ruins suggest a fake Babylon, evoking echoes of Borges’ “The Library of Babel” in their enigmatic, labyrinthine significance. The mention of other burned temples alludes to the cyclical destruction and rebirth that underpin the story’s themes. Borges’ story evokes the adventure and mysticism found in H. Rider Haggard’s tales of exploration and lost civilizations. Like Xenophon’s Anabasis and its tale of 10,000 mercenaries, “The Circular Ruins” portrays an epic journey, albeit one of the mind and spirit rather than physical conquest. The story’s setting feels like an aftermath of disaster, where the ruins represent both destruction and the potential for renewal. The narrator’s solitude reflects yet another abandoned village, a hallmark of Borges’ settings steeped in mystery and decay. The imagery could also evoke the post-apocalyptic aesthetic of the 1979 Walter Hill movie The Warriors with its surprisingly optimistic version of New York where chaos still holds potential for transformation.

In the Gnostic cosmogonies, a red Adam who cannot stand is a flawed creation, paralleling the dreamed man as an imperfect reflection of his creator. Borges evokes the idea that the world was created by the demiurge, a secondary deity whose imperfect work echoes the narrator’s own creation. In this, the story makes connections to ancient tropes and anticipates future ones:

- It resonates with themes from Valis by Philip K. Dick, where creation, divinity, and human perception intertwine in a metaphysical exploration. The narrator’s act of creation feels like an addendum to the creation story, presenting a personal, recursive mythology.

- Lilith, as a figure of unorthodox creation, serves as a parallel to the dreamed man, an alternative version of humanity’s origins.

- The geopolitical urban legend about red mercury echoes the alchemical undertones of the tale, where transformation and secrecy play central roles. Alchemical texts resonate with the story’s themes of creating life from an idea, turning intangible thoughts into tangible forms. The cold fusion of terrorism, like the narrator’s dream, represents a dangerous and explosive act of creation with unforeseen consequences.

- The dreamed man parallels a golem, a man made out of clay but without a soul, questioning the essence of humanity. The narrator’s creation recalls Adam of dust from Genesis but is ultimately an Adam of dreams, born from imagination rather than divine breath. The wizard is the dreamer, embodying both the power and the isolation that come with the act of creation.

Borges was the darling of the literary set when he was alive, celebrated for his masterful blend of erudition, philosophy, and imagination, and he is still a god of modern literature The story exemplifies Borges’ hallmark intertextuality, drawing on myths, religious texts, and literary references to deepen its meaning. Paradoxically, Borges’ made-up quotes and citations, a trademark of his style, lend “The Circular Ruins” an air of scholarly parody, blending fiction and reality. Much like H.P. Lovecraft, Borges’ works often parody 19th-century scholarship with their meticulous yet fictional sources.

The story’s themes evoke a clash of blades vs. brambles—sharp intellectual concepts intertwined with the messy, tangled nature of dreams. Borges, like Poe the prankster, injects wit and irony into his work, creating moments of puckish and wry humor amidst serious themes. At the same time, the philosophical undertones of the story recall the works of Herman Melville, blending grand existential questions with intricate, extraordinary sentences. Borges’ writing is puckish and wry, laced with a sense of mischief even as it reaches for profound truths. The narrative of “The Circular Ruins” itself represents an apotheosis, where the narrator ascends to a godlike role as a creator, only to discover he is also a creation.